from what i'm reading this is a relatively new field...here's some definitions. it's long and a little science-y, but super interesting:

Environmental psychology examines the interrelationship between environments and human behavior. The field defines the term environment very broadly including all that is natural on the planet as well as social settings, built environments, learning environments and informational environments. When solving problems involving human-environment interactions, whether global or local, one must have a model of human nature that predicts the environmental conditions under which humans will behave in a decent and creative manner. With such a model one can design, manage, protect and/or restore environments that enhance reasonable behavior, predict what the likely outcome will be when these conditions are not met, and diagnose problem situations. The field develops such a model of human nature while retaining a broad and inherently multidisciplinary focus. It explores such dissimilar issues as common property resource management, wayfinding in complex settings, the effect of environmental stress on human performance, the characteristics of restorative environments, human information processing, and the promotion of durable conservation behavior. The field of environmental psychology recognizes the need to be problem-oriented, using, as needed, the theories and methods of related disciplines (e.g., psychology, sociology, anthropology, biology, ecology). The field founded the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA), publishes in numerous journals including Environment and Behavior and the Journal of Environmental Psychology, and was reviewed several times in the Annual Review of Psychology. A handbook of the field was published in 1987 (Stokols and Altman 1987).

There are several recurrent elements in the research literature that help to define this relatively new field. Understanding human behavior starts with understanding how people notice the environment. This includes at least two kinds of stimuli: those that involuntarily, even distractingly, command human notice, as well as those places, things or ideas to which humans must voluntarily, and with some effort (and resulting fatigue), direct their awareness. Restoring and enhancing people's capacity to voluntarily direct their attention is a major factor in maintaining human effectiveness.

Perception and cognitive maps - How people image the natural and built environment has been an interest of this field from its beginning. Information is stored in the brain as spatial networks called cognitive maps. These structures link one's recall of experiences with perception of present events, ideas and emotions. It is through these neural networks that humans know and think about the environment, plan and carry out their plans. Interestingly, what humans know about an environment is both more than external reality in that they perceive with prior knowledge and expectations, and less than external reality in that they record only a portion of the entire visual frame yet recall it as complete and continuous.

Preferred environments - People tend to seek out places where they feel competent and confident, places where they can make sense of the environment while also being engaged with it. Research has expanded the notion of preference to include coherence (a sense that things in the environment hang together) and legibility (the inference that one can explore an environment without becoming lost) as contributors to environmental comprehension. Being involved and wanting to explore an environment requires that it have complexity (containing enough variety to make it worth learning about) and mystery (the prospect of gaining more information about an environment). Preserving, restoring and creating a preferred environment is thought to increase sense of well being and behavioral effectiveness in humans.

Environmental stress and coping - Along with the common environmental stressors (e.g., noise, climatic extremes) some define stress as the failure of preference, including in the definition such cognitive stressors as prolonged uncertainty, lack of predictability and stimulus overload. Research has identified numerous behavioral and cognitive outcomes including physical illness, diminished altruism, helplessness and attentional fatigue. Coping with stress involves a number of options. Humans can change their physical or social settings to create more supportive environments (e.g., smaller scaled settings, territories) where they can manage the flow of information or stress inducing stimuli. People can also endure the stressful period, incurring mental costs that they deal with later, in restorative settings (e.g., natural areas, privacy, solitude). They can also seek to interpret or make sense of a situation as a way to defuse its stressful effects, often sharing these interpretations as a part of their culture.

Participation - The field is committed to enhancing citizen involvement in environmental design, management and restoration efforts. It is concerned not only with promoting citizen comprehension of environmental issues but with insuring their early and genuine participation in the design, modification and management of environments.

Conservation behavior - The field has also played a major role in bringing psychological knowledge to bear upon the issue of developing an ecologically sustainable society. It explores environmental attitudes, perceptions and values as well as devise intervention techniques for promoting environmentally appropriate behavior.

Scope

Although "environmental psychology" is arguably the best-known and more comprehensive description of the field, it is also known as environmental social sciences, architectural psychology, socio-architecture, ecological psychology, ecopsychology, behavioral geography, environment-behavior studies, person-environment studies, environmental sociology, social ecology, and environmental design research; each advanced by different researchers, sometimes used interchangeably, sometimes with recognized gaps and overlaps between the terms. This multidisciplinary field draws on work in a number of disciplines including anthropology, geography, ekistics, sociology, psychology, history, political science, engineering, planning, architecture, urban design and, of course, aesthetics.

The varied names for the field accurately reflect an ongoing debate about its proper scope, for example, whether or not it includes study of human interaction with the natural environment. "Environmental design" is generally understood to describe design activities focused on the natural environment and sustainability as well as concern with the planned environment which humans build - the "artificial" or designed physical environment - and its ability to meet community needs. Only a small portion of the built environment is attributable to architects, so a focus on "architectural psychology" is seen as too narrow. Generally speaking, individuals associated with the field are interested in better understanding the relationships between people and their environments so that this knowledge can be applied to problematic real-world situations.

Proxemics

In the mid 1950s anthropologist E. T. Hall wrote "The Hidden Dimension" which developed and popularized the concepts of personal space and his more general name for this field, proxemics. He defined proxemics as, ". . . the study of how man unconsciously structures microspace - the distance between men in the conduct of daily transactions, the organization of space in his houses and buildings, and ultimately the layout of his towns."

Hall defined and measured four interpersonal "zones":

. intimate (0 to 18 inches)

. personal (18 inches to 4 feet)

. social (4 feet to 12 feet)

. public (12 feet and beyond)

In "The Hidden Dimension" he famously observed that the precise distance we feel 'comfortable' with other people being near us is culturally determined: Saudis, Norwegians, Milanese and Japanese will have differing notions of 'close'. In one of his best known empirical studies, Hall carried out an analysis of employee reactions to Eero Saarinen's last work, the John Deere World Headquarters Building.

Impact on the Built Environment

Ultimately, environmental psychology is oriented towards influencing the work of design professionals (architects, engineers, interior designers, urban planners, etc.) and thereby improving the human environment.

On a civic scale, efforts towards improving pedestrian landscapes have paid off to some extent, involving figures like Jane Jacobs and Copenhagen's Jan Gehl. One prime figure here is the late writer and researcher William H. Whyte and his still-refreshing and perceptive "City", based on his accumulated observations of skilled Manhattan pedestrians, steps, and patterns of use in urban plazas.

No equivalent organized knowledge of environmental psychology has developed out of architecture. Most prominent American architects, led until recently by Philip Johnson who was very strong on this point, view their job as an art form. They see little or no responsibility for the social or functional impact of their designs, which was highlighted with failure of public high-rise housing like Pruitt Igoe.

Environmental psychology has conquered one whole architectural genre, although it's a bitter victory: retail stores, and any other commercial venue where the power to manipulate the mood and behavior of customers, places like stadiums, casinos, malls, and now airports. From Philip Kotler's landmark paper on Atmospherics and Alan Hirsch's "Effects of Ambient Odors on Slot-Machine Usage in a Las Vegas Casino", through the creation and management of the Gruen transfer, retail relies heavily on psychology, original research, focus groups, and direct observation. One of William Whyte's students, Paco Underhill, makes a living as a "shopping anthropologist". Most of this most-advanced research remains a trade secret and proprietary.

Density and Crowding

As environmental psychologists have theorized that density and crowding can have an adverse effect on mood and even cause stress-related illness. Accordingly, environmental and architectural designs could be adapted to minimize the effects of crowding in situations when crowding cannot be avoided. Factors that reduce feelings of crowding within buildings include:

. Windows, particularly openable ones, and ones that provide a view as well as light

. High ceilings

. Doors to divide spaces (Baum and Davies) and provide access control

. Room shape: square rooms feel less crowded than rectangular ones (Dresor)

. Using partitions to create smaller, personalized spaces within an open plan office or larger work space.

. Providing increases in cognitive control over aspects of the internal environment, such as ventilation, light, privacy, etc.

. Conducting a cognitive appraisal of an environment and feelings of crowding in different settings. For example, one might be comfortable with crowding at a concert but not in school corridors.

. Creating a defensible space (Calhoun)

Noise

Noise increases environmental stress. Although it has been found that control and predictability are the greatest factors in stressful effects of noise; context, pitch, source and habituation are also important variables [1].

Personal Space and Territory

Having an area of personal territory in a public space e.g. at the office is a key feature of many architectural designs. Having such a 'defensible space' (term coined by Calhoun during his experiment on rats) can reduce the negative effects of crowding in urban environments. Creation of personal space is achieved by placing barriers and personalising the space, for example using pictures of one's family. This increases cognitive control as one sees oneself as having control over the entrants to the personal space and therefore able to control the level of density and crowding in the space.

Environmental Cognition

Environmental cognition (involved in human cognition) plays a crucial role in environmental perception. The orbitofrontal cortex in the brain plays a role in environmental judgment.

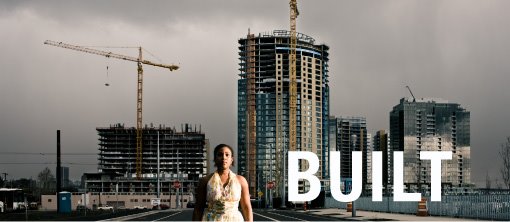

A Show / A Public Conversation / A Participatory Civic Planning Adventure

interesting links and articles

- Pica Blog Response to BUILT

- BUILT Review from The Oregonian

- Radio interview with Michael Rohd about BUILT

- Portland as a bubble? Article...

- BUILT PRODUCTION BLOG

- Brief cellphone video from our Hartford performance/civic event with Hartbeat Ensemble at City Hall in Hartford, CT on June 10, 2008

- Cabrini Green residents and the Chicago "Plan"

- Gentrification and "Upzoning" in the City

- Homelessness in Portland- Mercury Blog post, and comments

- List of dozens of recent articles that pertain to mixed-income housing, the Plan for Transformation, and the displacement that resulted from this plan

- LISTEN: public housing/gentrification panel

- michael rakowitz interview...

- NPR story on BUILT events in Hartford

- Portland SOWA Artist-In-Residence program

- TBA Festival in Portland

- urban to suburban migration- culture and tension

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Very informative and a clear read. Just what I was looking for in an introduction to this area of interest. Thank You. Perhaps further elaboration emphasizing some more on the known impacts of environmental stressers to further enlighten the cause effect and importance of understanding in a world growing in density and stimuli.

Hi, I am writing my diploma work on environmental psychology (and I come from Czech republic) and I cannot find ANYWHERE any good original sources that would say at least a little about the scope - related fields of EP. You mention this in your paper, could you please be so kind and tell me where I could find something on this topic? I know about Altman, Stokols and their hadbook, unfortunatelly this is not reachable in my country... Thank you for any help and for this article as well.

Post a Comment